More than 45 teachers from 15 schools in Chubut Province, Argentina, participated in the first training to launch our newest capacity building partnership: the YouthEnergy project.

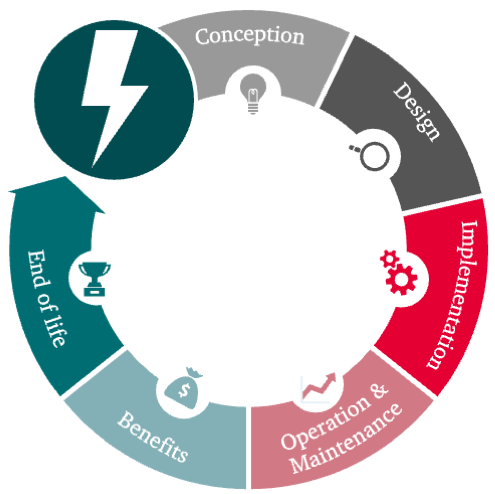

Lessons Along the Project Cycle

What are the key factors for ensuring the sustainability of energy interventions aimed at strengthening rural livelihoods? Over the last decade, the WISIONS initiative has supported community-based projects applying diverse renewable energy solutions within rural contexts in many different countries. We have learned lessons from these experiences in the field – both through our own research and by promoting reflection and mutual learning with and between local energy practitioners. This wealth of knowledge is available in various publications and resource materials and this article provides a concise summary of some of our key findings. It is structured along the general project cycle of energy interventions: from the planning phase of a project or programme to the end of life of the installed energy systems.

Conception

At WISIONS we understand energy as a means to secure or improve people’s livelihoods. Therefore, one of the main tasks in the very early phase of an energy project is to develop a better understanding of people’s current living circumstances and, in particular, of the values, aspirations, expectations, capacities and capabilities of local actors. Key factors to consider in the programme conception phase include:

- Clarifying the capacities and resources that are already available and how to expand or improve them;

- Identifying opportunities to use existing structures to effectively enable or secure access to renewable energy services and the areas where access to sustainable energy can have the greatest impact on the lives of people and communities;

- Creating partnerships with stakeholders who can contribute their own expertise to identify and develop these types of opportunities (e.g., in health, agriculture, education, craft and trades, female empowerment, etc.).

Further reading:

- The diffusion of sustainable family farming practices in Colombia: an emerging social-technical niche?, in: Sustainability Science, Volume 13, 2018, Pages 829-847

- Webinar: Setting the Scene – maximizing the impacts of energy access on people’s development opportunities

Design

An energy intervention necessitates changes in the daily practices of individuals and communities. This might include altering (or even abandoning) existing habits in energy use and/or adopting completely new practices. Therefore, a balance between the current structures and the future potential/desired outcomes is key when designing the detail of an energy project. Key lessons to consider in the programme design phase include:

- Formulating agreements at the outset about the future management model of the systems to be implemented (i.e., the actors involved and their roles and responsibilities) to ensure the continuous and sustainable operation of the technology after completion of the project;

- Using participatory tools to involve the local population in the design phase. This helps to promote project “ownership”, which increases the likelihood of sustainable change taking place;

- Exploring and including potential future demand developments by involving the local population and discussing their perspectives;

- Wherever possible, applying technologies that have already been used in similar conditions.

Further reading:

- How effective are small-scale energy interventions in developing countries? Results from a post-evaluation on project-level, In: Applied Energy; Volume 135, 15 December 2014, Pages 809-814

- A cross-sectional review: Impacts and sustainability of small-scale renewable energy projects in developing countries, In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews; Volume 40, December 2014, Pages 1-10

Implementation

Many types of changes are initiated in this phase, from the construction and installation of technical equipment to the establishment of organisational structures/business models and the adoption of new daily practices. It can be seen as a rather contradictory in-between state: on the one hand, it holds the promise of something new and beneficial, while on the other hand it means having to deal with the uncertainty associated with any process of change. Crucial lessons for dealing with this challenging phase include:

- Accounting for the experimental nature of project implementation; i.e., ensuring the flexibility to react to changes of various kinds (technical/managerial/external);

- Ensuring transparent communication at all times with all actors involved and especially with the affected local population;

- Integrating the existing organisational structures of local communities (e.g., cooperatives, committees, user groups, etc.) in as many implementation activities as possible. This can help not only to promote local “ownership” of the project but also to build local capacity to manage the system after completion of the project;

- Defining and establishing the configuration of the management model by this stage at the latest (i.e., the structure of actors, roles and responsibilities) to ensure the continuous operation of all the new systems and services provided by the project;

- Embedding regular monitoring and reflection of the project activities during this phase.

Further readings:

- Introducing Modern Energy Services into Developing Countries: The Role of Local Community Socio-Economic Structures, In: Sustainability; Volume 4 (3), 5 March 2012, Pages 341-358

- A cross-sectional review: Impacts and sustainability of small-scale renewable energy projects in developing countries, In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews; Volume 40, December 2014, Pages 1-10.

Operation and Maintenance

The importance of allocating the necessary resources to ensure the operation and maintenance of the systems deployed as part of the energy interventions cannot be overestimated. Two main lessons should be considered for operations and maintenance:

- Planning sufficient activities to build local capacities for the management, operation and basic maintenance of the system;

- Ensuring that after-sales services for all the technical components used in the project are familiar and available to as many local stakeholders as possible.

With regard to operations and maintenance, the ideal scenario is for a system or network of technical services to evolve. This should comprise several levels of technical expertise: from basic operation and preventive maintenance by local operators in the villages, to more advanced technicians covering small regions and service departments of technology supply companies covering whole countries. However, private companies alone are unlikely to be able or willing to finance the establishment of such systems. A systemic and multi-stakeholder approach is necessary.

Moreover, in our experience further challenges can arise:

- Migration: villagers who receive education and training tend to have a better chance of finding employment in other (non-rural) places. Accordingly, they often migrate – causing a lack of capacity for operating and repairing the local energy system;

- Insufficient business: the provision of services for distributed renewable energy technologies may not generate enough business for specialised technicians or workshops.

A “systemic and multi-stakeholder” approach is extremely important for overcoming these challenges.

Further readings:

- Rural electrification with household wind systems in remote high wind regions, In: Energy for Sustainable Development; Volume 52, October 2019, Pages 154-175

- Understanding the diffusion of domestic biogas technologies. Systematic conceptualisation of existing evidence from developing and emerging countries, In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews; Volume 74, July 2017, Pages 1287-1299

Drawing benefits from energy access

As previously indicated, the goal of energy access interventions is to make a positive impact on people’s quality of life. Currently, the focus is often on improving those aspects of people’s lives that are linked to the creation of economic wealth: the so-called productive uses of energy. A key lesson in this regard is that energy access alone is often not sufficient for improving productivity in rural areas. Therefore, projects and programmes should also include activities that address the following three aspects:

- Facilitating investment in additional appliances and other physical infrastructure. For instance, a good solar pump alone will not improve a farming system. Further investment in a better irrigation system or in greenhouses would probably be necessary to enable the farmers to increase their productive activities;

- Improving (or promoting new) productive skills. In the previous example this could mean, for example, teaching new techniques for growing vegetables in greenhouses or providing knowledge about other crops that could be cultivated with the available irrigation;

- Improving (or promoting new) entrepreneurial skills and access to markets. Local markets often become saturated very quickly, so knowledge and skills for bringing products to other markets are key for making a significant impact not only on productivity but also on people’s incomes.

Similarly, reliable energy services are also critical for public services, such as health and education. However, energy alone cannot improve these services; the following are also necessary:

- Appropriate appliances (tools);

- People with skills for making the most out of those tools (human capital).

Consequently, expertise and partnerships beyond the energy sector are required to leverage the benefits of energy in other sectors (e.g., health, agriculture, education, craft and trade). Or looking at the issue from an alternative angle: energy can be seen as an “enabler” of other development issues, but accompanying interventions in these sectors are necessary to reap the full potential of energy access.

Further readings:

- Productive use of energy – Pathway to development? Reviewing the outcomes and impacts of small-scale energy projects in the global south, In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews; Volume 96, November 2018, Pages 198-209

- Impact pathways of small-scale energy projects in the global south – Findings from a systematic evaluation, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 95, November 2018, Pages 84-94

End of life

Finally, energy provision requires the installation of diverse types of technical components – all of which have a limited operating life. An important issue to consider is what should happen to those components once they have reached their “end of life” to ensure the overall sustainability of energy access interventions. This is not a new topic, but it still lacks the attention it deserves. We must also admit that this issue has so far not gotten enough attention in the projects supported by WISIONS. There are two main general approaches to consider:

- Supporting the establishment of appropriate recycling systems in the countries where the uptake of decentralised renewable energy technologies is increasing;

- Promoting the application of circularity by design in the value chains of decentralised renewable energy technologies.